Eight decades of rebuilding the Saski Palace

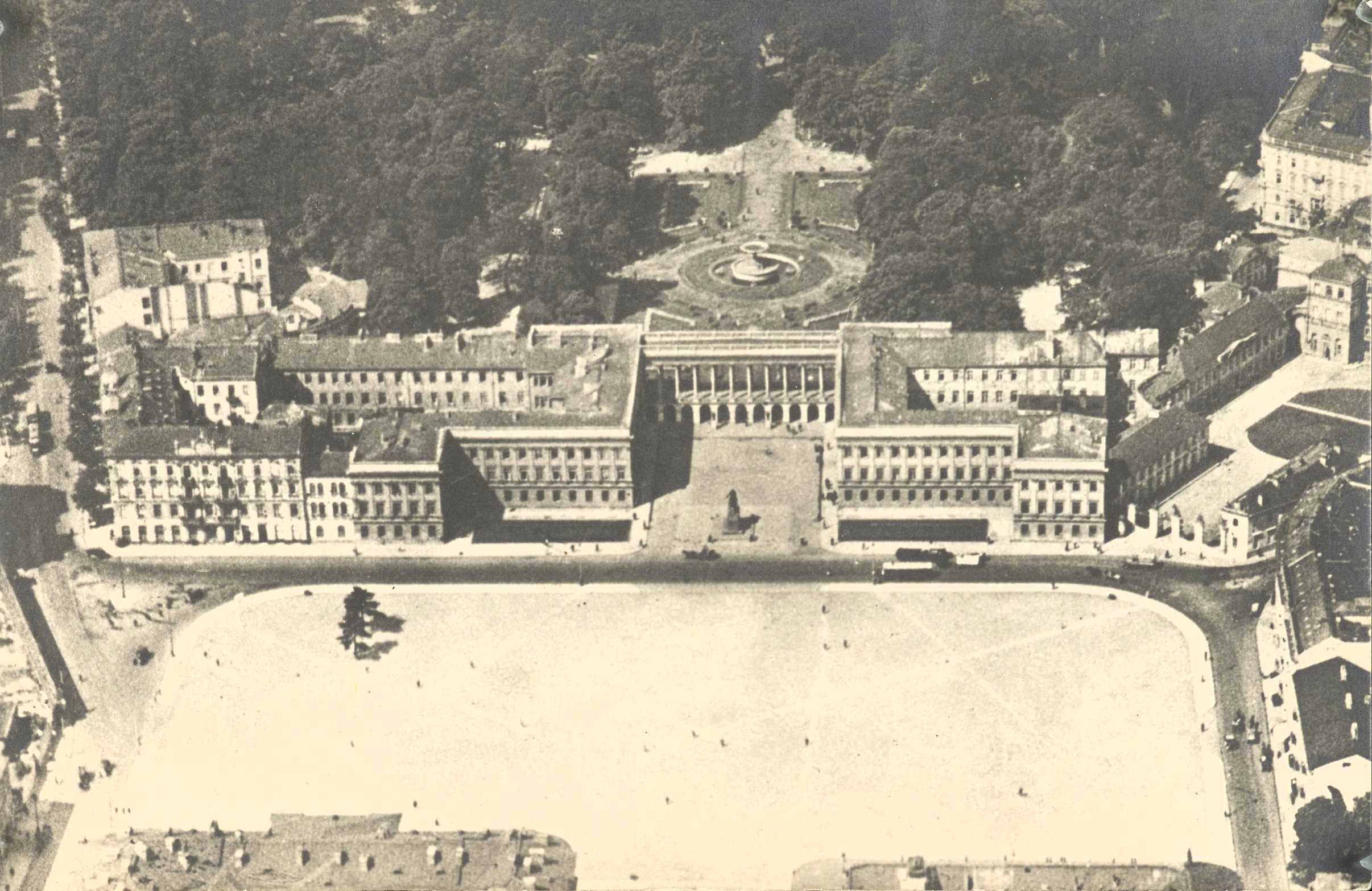

In December 1944, two landmarks disappeared from the panorama of Warsaw: the Saski Palace and the Brühl Palace. Practically from the same moment we can track the story of their reconstruction, as the Capital Reconstruction Office (BOS) was established in February 1945, while in November it was decided that the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier - until recently incorporated into the colonnade of the Saski Palace - would be reconstructed in the form of a partial ruin. The palace itself was to wait “for a while”, although as early as March 1946 Jan Zachwatowicz and Piotr Biegański, architects from the Department of Historical Architecture of the BOS, appealed in the press for the quickest possible reconstruction of “the entire frontage of the square in the old outline within the section of the Saski Palace and the Ossoliński [Brühl] Palace.” Eight decades later, after six architectural competitions, numerous projects, concepts and community initiatives – it is high time to rebuild what has been lost.

The Saski Palace and the Brühl Palace lay in ruins because of the deliberate campaign of the German occupying forces to destroy Warsaw, which, like the entire occupation period, did not erase the symbolism and significance of the place where the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was located since 1925. The first guard of honour at its ruins after the war was set up as early as 17 January 1945. That same year, the future of the monument, the square and the city as a whole were being decided. In November 1945 – by order of the then Marshal Michał Rola-Żymierski – a committee of officers of the Warsaw Military District issued an opinion on the location and form of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. It was decided to leave the mausoleum on the same site, but as a partial ruin of the former complex. In February of the following year, work was commissioned to the architect Zygmunt Stępiński.

Reconstruction of the Tomb of The Unknown Soldier

The Provisional Government decided to celebrate the first anniversary of the victory in World War II with a grand parade on the former Piłsudski Square. However, the ruins of the Saski and Brühl Palaces and the short time for preparations complicated the matter. At the time, BOS did not have any ready-made plans or decisions on the shape of this part of Warsaw, but the recommendation of rebuilding the demolished palaces was raised. Above all, however, there was an attempt to stop the hasty removal of the remains of the buildings by the military, which was carried out without the necessary research and documentation. This topic was discussed both within the BOS and presented to the military overseeing the work, which, however, had no impact on the activities carried out in the square. Interventions on the matter included a letter to Bolesław Bierut himself from the then Dean of the Faculty of Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology:

In view of the complete elimination, by means of demolition and blowing up, of the remains of the outstanding architectural monuments of the former Saski Palace and the former Ossoliński Palace destroyed by the German occupant, in the Saxon Square, the Council of the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology, concerned for the fate of the few remnants of monuments of national culture, requests that the form and scope of the current work be changed so that the remains of these monuments are respected.

In the second half of March 1946, work on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier began according to the guidelines and concepts of the military. The earlier decision to leave the “monument-ruin” in place, to design decorative grids with a new decoration – the Grunwald Cross – was upheld, as well as to move the battlefield plaques and add new ones listing the battles of World War II. It was not until 23 March that the Historic Architecture Department of the BOS delegated Zygmunt Stępiński “to the project of cleaning up the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and its surroundings”. In the end, the works consisted in the conservation of the preserved part of the monument, the construction of the missing arcade on the side of the Saxon Garden, the reconstruction of balusters and fragments of columns and the design of new metalwork details and commemorative plaques. The result of the work, a permanent ruin-monument with altered symbolism, was ready on 9 May 1946.

Despite protests, the surviving walls of the Saski Palace and the remains of Malhome’s corner townhouse at 6 Królewska Street, as well as the surviving plinth of the monument to Prince Józef Poniatowski or the pillars of the Brühl Palace gate, were demolished for the ceremony on the square, while the rest of the ruins of the palace remained on site until the early 1950s. More than 35,000 m3 of rubble was removed from the site, although quite a few items were undamaged and could be used for reconstruction. These works therefore led to the loss of historic substance and original elements. It is likely that instead of taking the rubble to a special site, it was used to reinforce the banks of the Vistula River. The nature of the decisions that took place among the communist military authorities over the course of several months in 1946 clearly indicate a reluctance to rebuild the palaces. What is more, accounts of the discussions on the subject indicate that the design of the most important monument – the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier – was drawn up in the offices of these authorities and its symbolism was distorted for the next 50 years. The square was renamed Victory Square and its form deprived of its most important buildings for the next 80 years.

The first competition, i.e. first the Brühl Palace

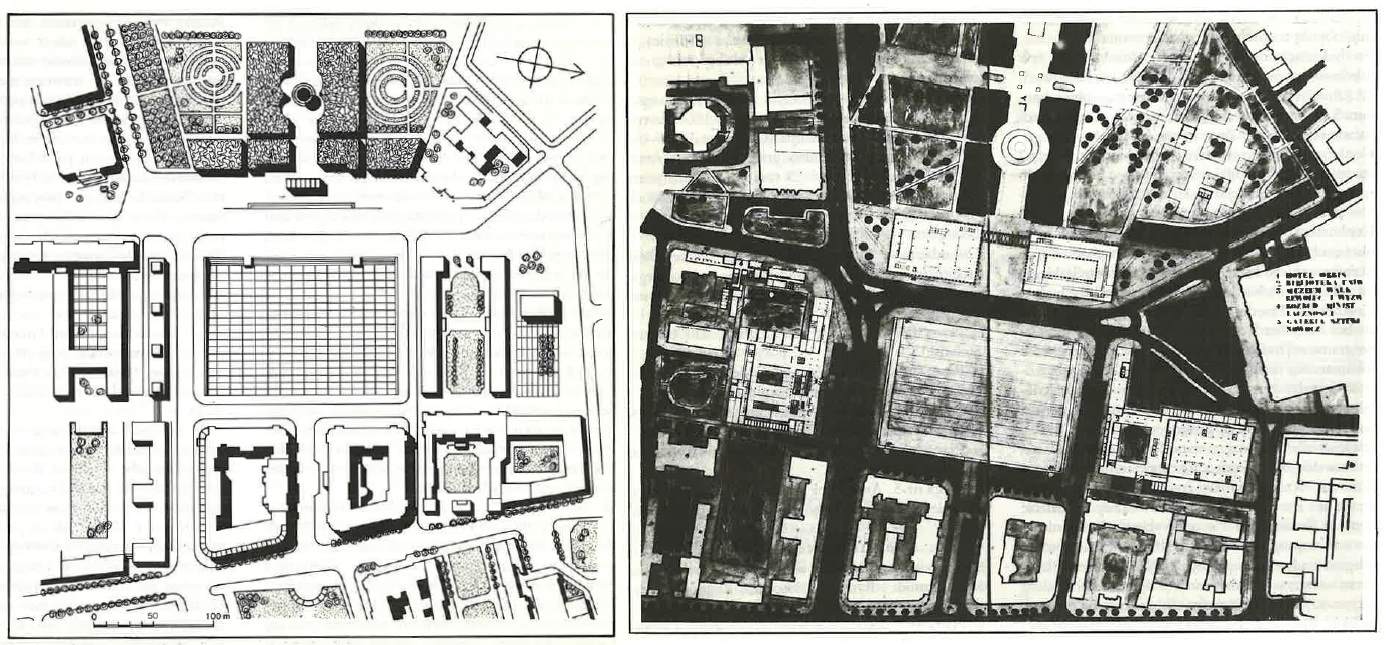

Over the decades, many attempts were made to fill the void. Announced in 1947 by the Association of Architects of the Republic of Poland (SARP), the competition for the design of Victory Square, the Saxon Axis and the design of the Polish Army House was a closed one. Seven teams of architects were invited to take part and given considerable freedom. The square was to be used for local vehicle and pedestrian traffic, and the nearby Europejski Hotel and the modernist “House without Edges” were to be preserved. Five of the submitted projects proposed the reconstruction of the Brühl Palace, but none envisaged the return of the Saski Palace in its entirety. As there was no winning project, the architects distinguished by the competition jury, that is Bohdan Pniewski and Romuald Gutt, jointly developed post-competition concept in which they proposed rebuilding the colonnade of the Saski Palace itself, omitting its wings.

Another project was presented in 1950 by Piotr Biegański. His team of architects closely followed the historical composition of the square and proposed the reconstruction of the main body of the Brühl Palace with additional space for a garden on the site of Fredry Street. The Saski Palace was also to return: with simplified courtyards, but with a monumental colonnade. Later that year, Biegański won a second distinction in the SARP competition for the design of the Grand Theatre building, where he continued to raise the need to rebuild the Saski Palace and to recreate a more intimate space.

A Museum of Revolutionary Struggle instead of the Palace

For more than a decade it seemed that nothing would come of the project, but in 1964 SARP announced another competition: for a study of the urban concept of Victory Square and parts of the Powiśle area in Warsaw. The guidelines mainly concerned the location of the buildings for the Central Council of Trade Unions, the Ministry of Communications or the Museum of Revolutionary and Liberation Struggles – a special one, as it was to be built near the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. As one might imagine, the museum was to be built on the former site of the Saski Palace. The winning design by J. Czyż, J. Furman, J. Józefowicz and A. Skopiński, however, largely envisaged the preservation of its form – two buildings surrounding the monument, connected by a beam at the level of the upper cornices. Interestingly, the form of the Tomb would be reduced only to the slab itself. The site of the former Brühl Palace was to be occupied by the university library and a residential building for employees. Due to lack of funds, the project failed.

New architecture, old buildings

The 1970s saw new trends in architecture, particularly in the West, where historicist forms and restorations of historic buildings were gaining popularity. In January 1971, the long-awaited decision to rebuild the Royal Castle in Warsaw was announced, and the following year SARP announced a competition for the design of Victory Square. Let us draw attention to one of the provisions of the regulations: The programme section may also consider the possibility of reconstructing historic complexes that do not exist today (including the headquarters of the former General Staff) and the possibility of adapting these buildings for the postulated programme. Even though the winning design by B. Gniewski and B. Kosecki partially met the above-mentioned requirement, it was never implemented.

The impulse for the next competition, which took place at the end of the 1980s, was to prepare a design for a new “Orbis” hotel and congress centre, together with a study for Victory Square. The architects had a great deal of freedom in arranging the space, although with some limitations: they had to plan a car park under the square, preserve the primacy of the historical Saxon Axis and maintain the appropriate scale of architecture. The winning work was by O. Jagiełło, M. Miłobędzki and J. Szczepanik-Dzikowski. In their proposal, they repeated the line of pre-war buildings along Ossolińskich and Wierzbowa Streets through the new hotel building, the wing of which reached all the way up to the Great Theatre. They also returned to the idea of rebuilding the main body of the Brühl Palace and its decorative gate, but without the outbuildings.

As can be seen, the space of Piłsudski Square (then still Victory Square) still needed a setting, and the subject of its development returned like a boomerang, undermining the thesis of a strong desire to keep the square empty as a metaphor for the tragedy of World War II. The symbolism of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in the form of a permanent ruin has also been eroded over time, as successive generations were no longer familiar with its full form in the arcades of the Saski Palace.

After 1989 - The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier should look like it used to be

The political changes at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s did not omit the square, which was given the new-old name of Marshal Józef Piłsudski in 1990. A while earlier, in the autumn of 1989, on the initiative of, among others, Witold Lisowski and Aleksander Gieysztor, the Foundation of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was established with the aim of rebuilding the monument in its original form together with the Saski Palace. As Gieysztor stated in a television programme: I believe that this initiative [the restoration of the Saski Palace] will be met with a response from the entire Nation. It is high time to give this place, sacred to our history, the highest rank.

This was undoubtedly a change of approach. Instead of only tidying up of the square, the restoration of the original shape of the Tomb – naturally more complete and richer in terms of decoration compared to the ruin preserved in 1946 – became paramount. Although the postulate was not implemented, the idea resonated with the public, as evidenced, for example, by another competition announced in 1993. As before, it stipulated maintaining the urban layout of the Saxon Axis, but additionally referencing the historical buildings from 1939. The concept most fully realising this requirement was presented by the architects from PKZ “Zamek”, who proposed both the reconstruction of both the Brühl and the Saski Palaces and modern forms in the place of the townhouses on Królewska Street and along Ossolińskich and Wierzbowa Streets. The concept also included suggested functions for the buildings: the Saski Palace would house the Museum of Polish History, while the Brühl Palace would welcome visitors as a luxury hotel. Once again, however, despite the development of further concepts, the Saski Palace was successfully rebuilt in 1999 - but only with LEGO bricks.

A new chance for reconstruction appeared on the horizon with the arrival of the year 2000, when the Saski Palace was to become the seat of the National Bank of Poland, and history in all its glory, i.e. the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was to return to the Brühl Palace. Again, financing got in the way and the idea failed. However, Warsaw did not abandon the project entirely. In 2005, after a series of changes and unsuccessful tenders, the commercial partnership, which for a while seemed to be a solution to the financing problem, was abandoned. In mid-2006, a contract was signed for the reconstruction of the Saski Palace and the revitalisation of Krakowskie Przedmieście Street. Almost immediately, archaeologists entered the site of the former Saski Palace. Their research resulted in the acquisition of a total of over 40,000 artefacts and the oldest fragments of the cellars were entered into the register of monuments. And then there was another pause. In 2008, the investment was suspended, the exposed cellars were buried, and funds were redirected to the construction of the second metro line, the Northern Bridge and the organisation of Euro 2012.

A palace for the centenary of independence

Ensuing disappointment became an impulse for a group of enthusiasts of history and architecture who in 2012 founded the Saski 2018 association. Its members set themselves the goal of bringing about the restoration of the Saski and Brühl Palaces for the 100th anniversary of Poland’s independence. The organisation’s activities, such as historical education or the promotion of the idea of reconstruction among the public as well as local and central administration, were recognised and in 2013 the association received the “S3KTOR” award for the best non-governmental initiative of the year.

Over the following years it became clear that the palace would not be built so quickly, so the goal had to be reformulated. In 2017, the association organised a meeting with the descendants of the Polish mathematicians and engineers who broke the Enigma cipher while working in the Saski Palace. Their appeal to the highest authorities of the Republic of Poland to resume the reconstruction of the Saski Palace and to include the decision in the programme of celebrations of the 100th anniversary of Poland regaining its independence was accepted. On 11 November 2018, the restoration of the Saski Palace was inaugurated by the President of the Republic of Poland during the celebrations at Piłsudski Square, and the Pałac Saski sp. z o.o. company was established at the end of 2021. Its task is to prepare and implement investments in the restoration of the Saski Palace, the Brühl Palace and three townhouses at 6, 8 and 10/12 Królewska Street in Warsaw based on the Act of 11 August 2021 (Journal of Laws, item 1551). Work on Piłsudski Square is finally underway. The most recent – tenth – competition was finalised in 2023, and work on Piłsudski Square is finally taking place.

The story of the reconstruction of the western frontage of Piłsudski Square clearly shows that the emptiness of this space was not desirable. For almost 80 years, the topic of its development was discussed in subsequent competitions, concepts and initiatives. Although visions, forms and purposes differed, they agreed on one point: the square should not remain in the form from 1944, preserved in 1945. The arguments for symbolic emptiness lose their justification when one looks at the efforts of several generations of architects and urban planners. By contrast, arguments that raise the significance of the monument-ruin form prove misguided when we ask about its origins. With time, memory fades and the void ceases to speak. The reconstruction and restoration of the original form of the complex are an opportunity for a new chapter in history.

Authors: Maria Wardzyńska, Dominik Szewczyk

The article was published in "Stolica" magazine 3-4, March-April 2024